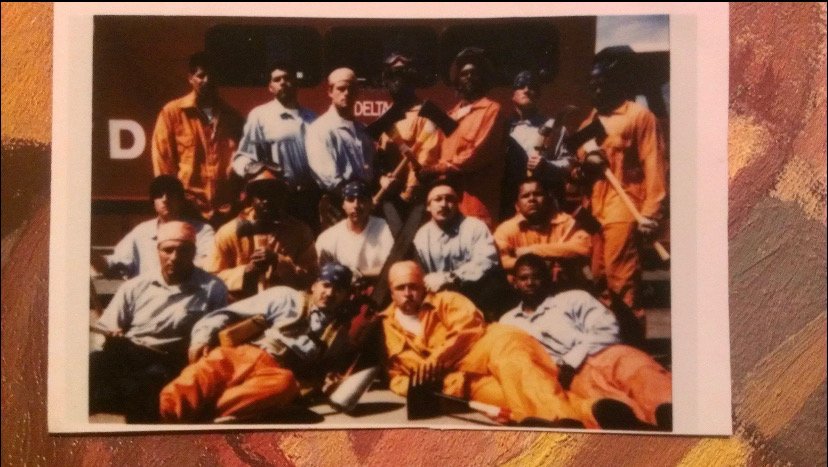

Mendocino County, 1996

The Fork Fire

The Fork Fire began as all fires do with a spark of ignition small and imperceptible to the eye. This in due course spreads to the available and willing fuel that is consumed and engulfed by the hunger of flame that follows its laws and reaches the potentials it is allowed. We were in the first wave of responders arriving in the mid morning. What we saw was a patch of about twenty yards of grey smoke in the center of the mountainside that was made up of heavy green fuel. We disembarked our truck and started rolling smokes and settling back into what seemed like what was going to be a washed call. By all appearances the fire seemed like it was going to be out by lunchtime. It was assumed that CDF would apply air assets and knock down the fire before it took off. As we sat and waited over the next hour no helicopters or tankers arrived and the blaze gained in strength and size. The coming afternoon winds built and fed the fire that now moved with speed and fury through ravines and chutes taking into the flame’s huge swaths of heavy brush and timber that passed the flames into the crowns of the conifers. The ridgeline went as far as the eye could see. The crews in the holding area began talking in hushed tones wondering why this fire seemed to be getting a free pass to turn into a monster. By three o’clock the mountainside was wildfire and near dusk we moved out to about four miles in front of the fires spearhead. Nothing made sense. It seemed possible that the area might be on a list for a burn because there seemed to be exceptionally heavy buildup of dead fuel. Swathes of tall trees and brush looked dry and explosive. We began to work as night fell. We cut hundreds of yards of line up and down steep ridges and ravines. The next morning the fire had attained a size where it was making its own weather in accordance with its needs, and it maximized the physical laws it would exploit to its advantages. This was a fact not lost on the people present. The main plume of smoke was sending embers high aloft into the atmosphere and landing them far and wide into untouched areas of fuel sparking ignitions of spot fires. These were the wild offspring of the main fire growing fast like children, individual, with each of them displaying a unique hunger and will to survive and flourish.

Our hand lines were impressive feats of destructive creativity but were of little concern to the fates and rampages of the fire. We cut a path in whichever direction we headed leaving bare mineral earth in our wake. Our crew was a twenty-headed locust that mercilessly mowed down whatever was in our way. It was relentless work and sometimes dangerous especially in the dark. Cutting line up steep slopes, brush would be cut away and thick chaparral that had held automobile sized boulders in its branches for years would release them thundering downhill. Trees would be cut and fall in unexpected directions because of variables that could not be seen or known. We had heard stories about disasters that had befallen other crews in the past. How when a crew walked off a line in the dark during a fire near Big Sur, a tree nearly a hundred feet tall that had been weakened in the burn fell on the crew that was filing out. Eight people were killed and two paralyzed. There were many ways to get injured on fires. Heat exhaustion, burns, smoke inhalation, lacerations, sprains, bruises, snake bites, massive exposure to poison oak, injuries from the hand tools which were kept razor sharp, and from the chain saws that could kick back and split open human flesh into gaping wounds.

Most of the work on a fire line is hard and monotonous that can turn into a kind of meditation concentrated on the work literally in front of you, built on the efforts of the person ahead of you and doing your part for the worker behind you to build upon. It was a metaphor put into muscle memory. Each tool had its character and people were assigned to them accordingly into a loose hierarchy. The chainsaw sawyers were point on the crew line and were the alpha positions. Each one worked with a puller who cleared away the cut fuel the sawyer had ripped through. A puller or swamper also kept the saws running well and the chains sharp. I was alternating as puller for Mouse while on the Fork Fire. I carried several bags of chains with me and a small, high velocity Stihl chainsaw that had a 12” bar that I kept slung on the back of my web gear. I had set a standard for myself that Mouse would always have the sharpest chains in the entire camp. I used downtime to turn each tooth into a razor. The chains were also constantly cleaned and oiled. I knew that it was a great danger to the sawyer to have a poorly maintained chain on their saw. If they did, they would then make adjustment to their cuts that should never have been made. I remembered a representative who had come from Stihl who showed us a video of what happens when a chainsaw hits a body. There was image after image of faces and bodies split in two, with wounds that you would never fully heal from if you survived. I found another form of meditation in the sharpening of chains, working them until I felt the metal give into its sweet spot where I knew without even checking that the tooth was critically sharp. My fingers had thin cuts all over them. I held them as badges of honor.

The other tools of the hand crew were the Pulaski, McLeod, and the shovel AKA the drag spoon. Each tool section is led by a strong member who will set the tone and tempo for the people following behind. The Pulaski is a tool that was developed in 1911 by Ed Pulaski a ranger from the United States Forest Service who was credited for taking actions that saved the lives of forty-five fire fighters in the Idaho Wildfires of 1910. The Pulaski was his innovation after this disaster in response to the lack of specialized fire fighting tools. Its design is a combination of an axe and an ultra-sharp cutter mattock- the horizontal element found on a pick. Five members of the hand crew use Pulaski’s and are strung behind the four- person chainsaw team. Their job is the removal of smaller brush and root balls left behind by the saws. Behind the Pulaski’s are five McLeod tools. The McLeod is a tool that was developed in 1905 by U.S. Forest Service ranger Malcolm McLeod at the Sierra National Forest. It is a heavily sharpened hoe with a tined rake that is descended from a traditional fire rake. These tools are responsible for the final finishing of the line, leaving the bare mineral earth of the firebreak. When Mouse would rotate off the line for rest, I would flip to number five McLeod position and the captain would exploit my spastic energy to ‘bite the tail of the line and finish with a bang’. The captain knew to give me copious amounts of sugar and coffee and I was good to go. He also knew that Rick Dawg the crew’s drag spoon at the end of the line was my Bunkie. Rick Dawg carried a razor-sharp shovel and did final mop up and quality control. He had this job because of his seniority and his laconic chill vibe. Nobody took it the wrong way when Rick Dawg told him to fix up the work. He wore his helmet at a perfect tilt that had style and an easy swagger. He would laugh at me and say, “Go Bunkie!” as I went furiously into my work not leaving a twig or blade of grass remaining in the fire line. On the ‘Fork’ I volunteered to stay on the line as long as possible and sleep dirty. In the three weeks I went to base camp only once after an incident that forced our evacuation.

About a week into the fire, we were inserted at the top of a ridgeline into a football field sized safety island that had been cut by another crew and heavy machines. We walked along a smaller trail for a quarter of a mile into the green to begin carrying out our orders to create a long firebreak. The fuel was so heavy and dense that it was nearly impossible to move. Progress into the brush was slow and backbreaking. About forty-five minutes after we started, we heard our crew call sign come on the radio chatter. Our Captain listened intently as we killed our saws and heard the spotter aircraft at the top stack of the air attack orbiting above us mechanically drawl, “Delta 5, Delta 5, evac to safety zone immediately, multiple spot fires are incoming on your location at speed of twenty to thirty miles per hour”. I looked at Mouse and pulled out the sheath and covered the bar of the chainsaw and while I did, the second order came over the radio to evacuate at a full run to the safety area. The part I had not heard from the spotter’s transmission was that two fast moving fires were converging. The main front had shifted from a sudden wind change and several spot fires which had started opposite of our line had joined and created a second front that now formed a pincer. The last hundred yards of the dash back to the safety island the smoke was extremely thick, and it was difficult to see the perimeter lines of the zone. There were two trucks parked in the center of the island and everyone headed for them knowing that it was the furthest point from the green. There was loud roaring as heavy brush and timber was consumed in fire, punctuated by the sound of green branches exploding in extreme heat. Then another sound appeared, a different kind of roar that came from a stampede of animals and creatures of the forest large and small running for their lives through the smoke, deer with terrified eyes and streams of rabbits and rodents that ran over my boots and on all sides of me. There was fire and great heat all around us. Then on the edge of the safety zone that faced the main slope of the mountainside that plunged downwards, an eerie sight erupted as the air distorted and wavered with veils of heat streaking upwards in great waves of seared oxygen, as at last the main head of the fire made its arrival to us. I was transfixed as the vibrating air incinerated, turning into a curtain of flame length that burst more than a hundred feet into the air as old growth trees ignited and exploded. The sound of the oxygen being swallowed by the fire made sounds I had never heard before or again. As I stood watching, the fire orders were shouted down the line to hit the deck and I wondered if we were going to have to deploy our fire shelters, which were also known as shake and bake bags. The heat continued to rise as we all hit the dirt. The radio in the truck was loud enough to hear the conversation between the Airtak spotter and the C-130 Hercules tanker who was en route to hit our location with a payload of retardant. Shouts once again went down the line to get prone and steady with hands overhead. On the radio the spotter said good luck and keep your head down. Seconds later a small guide aircraft streaked through the smoke no more than two hundred feet directly over our position and following close behind was the tanker that blacked out the sky with its enormous size and it unleashed three thousand gallons of brightly colored retardant on top of our position. The retardant smelled like ammonia and had the consistency of phlegm or raw eggs. The smell came from ammonium sulfate or diammonium phosphate that served as a fertilizer to help the re-growth of plants after the fire. The bright color came from ferric oxide that marked the drop area in reddish pink colors easily seen by the aircraft. The fire fighters in the drop zone were covered in the colorful slime. The tanker pilot and Airtak team had saved us from a probable shelter deployment or worse. We stood by as helitak copters landed and took some firefighters off the line. I was pulled for mop up duty around the perimeter of the safety zone and drove out from the line with the skeleton crew that was covered with ash and retardant. The truck drove out of the fire along a narrow dirt road through a forest that was still burning and dropping embers on our vehicle. It was a hellish looking landscape that was carbonized and deep black. I looked out of the window and wondered how long it would be until a green stem would pop out of the burned wasteland and begin the forest once again. I lit a cigarette and smoked and felt totally relaxed. When I came into the base camp it shocked me to see that a literal fire fighter city had been set up and there were many hundreds of fire fighters and support crews bustling about in their business. The clean crews in the base camp looked at us like we were aliens when we stepped off the truck. We were covered in filth and ashes and bright pink retardant that had blended into our orange prison nomex leaving us with a kind of grimy rainbow sherbet color. We were taken to the head of the food line and had our first real meal in a week.